In Parts I, II and III we discussed the events and issues leading up to the passage of the Act of Supremacy, which caused the English church to break ties with the Pope and Roman Catholic Church. In this post, we’ll discuss what happened afterward during the rest of Henry’s reign.

The Act of Supremacy was passed in 1534, separating the English church from Rome and placing the monarch as the head of the church. Opposition to the Act was punishable by death, as witnessed by the executions of Sir (now Saint) Thomas More. More, who became Lord Chancellor after Cardinal Wolsey’s fall from grace, and (also a saint)

Bishop John Fisher, a leading opponent of the breach with Rome refused to swear allegiance to Henry VIII as the head of the English Church. Fisher was executed in June of 1535 and More was executed in July of 1535, declaring on the scaffold that he died “the king’s good servant but God’s first.”

In January 1535 Thomas Cromwell, Henry’s Chancellor, became Vice-Regent in Spiritual Affairs, which allowed him to continue working on reforming the church of England. In 1536 the Dissolution of the Monastaries began. Lands were seized and sold to the nobility, who, its was reasoned, would be reluctant to support a return to Roman Catholicism if it involved giving up their land.

The dissolution did not go unnoticed among the locals, however, and in the north of England there was an uprising known as the Pilgrmage of Grace. This was a quite bloody uprising and is worthy of a post in an of itself, as is the Dissolution of the Monastaries.

So what happened theologically? In 1536 Parliament passed the Ten Articles which was a compromise, of sorts, between Catholics and the reformers. The sole sacraments were Baptism, the Eucharist or Holy Communion, and Penance. Purgatory became a non-essential doctrine. The prayers for the dead and calendar of the saints was continued, although some saints were left off the calendar.

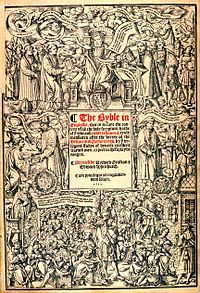

Most important during this time period was the requirement that a Bible in English was required to be kept in all churches. The “Great Bible” was a modification of the English

Bible by Miles Coverdale. This was replaced by the King James Bible in 1611, however the Coverdale Psalter can still be found in the 1928 Book of Common Prayer.

After the Ten Articles Cromwell continued to enforce reforming principles in England including destroying statues, images, and even the shrine of St. Thomas Becket in Canterbury.

All of this did not escape Henry VIII’s attention. Remember Henry was a contended Catholic and the direction of the English church troubled him. This was not lost on Cromwell’s opponents, of which there were many. Henry was also not very happy with Cromwell’s role in his arranged marriage to Annie of Cleves, whom he did not like.

Finally in 1539 the reforms were reversed with the passage of the Six Articles. Transubstantiation in the Eucharist, or the Catholic doctrine that Jesus is actually physically present in the consecrated bread and wine was upheld, the laity were not to be given wine at communion, clerical celibacy was enforced, monastic vows were to be honored, and confession was retained.

Cromwell fell from favor with Henry and was executed in 1539. There was no new Vice-Regent for Spiritual Affairs. Other events such as war with Scotland and France stalled any reform efforts.

Henry VIII died in January, 1547. At the time of his death, very little had actually changed. Mass was still said in Latin, communion was in one kind (bread), clerical celibacy was requirement and the traditional Catholic understanding of the seven sacraments was upheld. What had changed, though, was quite important. A lay person was the head of the Church. The clergy was subject to the laws of Parliament and Parliament had legislated religious doctrine.

It would take a new King, the “boy King” Edward VI, with a Regency Council of nobility who were sympathetic to the ideas of the Reformation, for the English Reformation to proceed further. With Cromwell gone, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer would step forward to lead the next stage of the Reformation, and that will be explored in Part V.

One month ago The Most Reverend Justin Welby was enthroned at the 105th Archbishop of Canterbury. If you missed his enthronement service you can watch it here. So here’s a good opportunity to go back to the sixth century and take a look at the first Archbishop of Canterbury, St. Augustine, the mission to England, and how that helped give us the English church as we know it.

Part I-The Missionary Journey

The idea for a missionary trip to Britain began with Pope Gregory the Great (590-604). Before Gregory the Great began pope in 590 he had encountered Anglian slave boys being being sold on the open market in Rome around 586. Tradition has it that Gregory was so moved by the plight of these boys that he purchased them, had them baptized and then educated so that they could eventually return to England as missionaries.

Its important to understand the religious landscape of England at the time. The invasions of the Anglos and the Saxons earlier in the fourth century had forced Roman Christians living in England to abandon Christianity in favor of the paganism of their invaders or flee westward into Wales. While there was evidence that some Christians did, in fact, remain in eastern Britain, those Christians, according to the Venerable Bede, the great historian of the early English church.

Gregory’s concern for the spiritual welfare of the English people continued to grow and, as Bede tells is, “he put in hand his long-cherished project.” He secured the support of a number of Christian monarchs for the mission including (now a saint) Queen Bertha, a Frankish Christian and the wife of (now also a saint) King Aethelbert of Kent, who at the time was a pagan.

In 596 Gregory the Great selected Augustine, who was a monk at the same monastery

on Coelian Hill where Gregory had served before becoming Pope, to lead the mission to England. As Augustine and his party traveled through Gaul they heard stories of the savagery of the English people and considered returning home. Pope Gregory wrote to Augustine advising him to continue telling him “the greater the labor, the greater will be your eternal reward.”

Part II-Landing in Kent

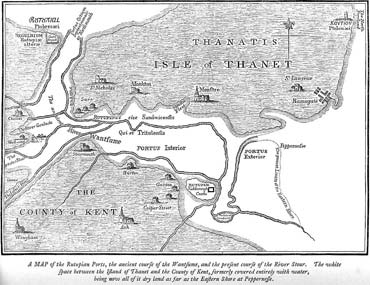

Map of the Isle of Thanet in medieval times. The channel between the isle and mainland closed off by 1500 making Thanet no longer an island.

Augustine and his party landed on the Isle of Thanet off the coast of Kent in early 597. King Aethelbert sent greetings to them and provided them with necessaries but did ask them to remain on the isle until he could have an audience with them. During their audience with Aethelbert, which was held out of doors for fear of the monks placing a magic spell upon the King, the monks sang a litany and preached to him. Aethlebert, according to Bede, told the monks that he could not “abandon the age-old beliefs that I have held along with the whole English nation.” He allowed the monks to come to the mainland and gave them a dwelling place.

Part III-The Conversion of England

Aethelbert would quickly convert to Christianity but did not require it of his subjects as he thought “the service of Christ must be accepted freely and not under compulsion.” Augustine became a bishop in the fall of 597 A.D. and during Christmas of 597 he and his fellow missionaries baptized 10,000 converts. Once Christianity had been established in Kent, Gregory instructed Augustine to send a bishop to York who would consecrate twelve more bishops and become an archbishop. The new archbishop would, however, remain subject to the authority of Augustine. Augustine also consecrated bishops of London and Rochester in 604 and it was planned that the Archbishop of Canterbury would move to London and this would become the primatial see, but this never occurred.

Augustine died in 604 and was buried outside the church of the Abbey of Saints Peter and Paul (now known as St. Augustine’s Abbey) as the church itself was not yet finished. Miracles were attributed to him and he was canonized a saint. His shrine, lost in the English Reformation, is now located in St. Augustine’s Ramsgate, a church of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Southwark, notable for its design by and burial place of the Victorian church architect Augustus Welby Pugin.

An important feature of Augustine’s episcopacy was how he (and Pope Gregory) handled local religious customs. When Augustine wrote to Gregory and asked him why customs differed in various churches, Gregory answered that Augustine should “select from each of the church whatever things are “devout, religious and right,” and to “let the minds of the English people grow accustomed” to them. Pagan temples were not destroyed, they were blessed, altars set up, and relics deposited there for use during celebration of the saints days which replaced pagan festivals.

Rivalry between Augustine and bishops from other parts of Britain resulted in Augustine not being able to unify the entire English church. While it would take centuries more to unify the church in England, Augustine’s and Gregory’s gift to us was the beginning of a change in the culture of Britain and a huge step forward in the development of the English church.

The Feast Day of Alfred the Great is celebrated today, October 26th. King Alfred, who lived from 849-899 was King of the West-Saxons of England. Alfred came to the throne in 871 and in 875 beat back an attack on England from the Danes. After their loss, the Danes attacked again in 876, 877, and 878 when Alfred finally defeated them. As part of their peace agreement with Alfred, the Dane’s leader, Guthrum, agreed to be baptized.

from 849-899 was King of the West-Saxons of England. Alfred came to the throne in 871 and in 875 beat back an attack on England from the Danes. After their loss, the Danes attacked again in 876, 877, and 878 when Alfred finally defeated them. As part of their peace agreement with Alfred, the Dane’s leader, Guthrum, agreed to be baptized.

Alfred made multiple contributions to English life in the areas of education, law, and religion. He is noted for translating the work of Pope Gregory the Great on pastoral care, the Ecclesiastical History of the English People by the Venerable Bede, a work which is readily available to this day. He also sought to appointed well qualified abbots and bishops, and took the spiritual care of his subjects very seriously. Because of his work in the area of religion and education, as well as helping to unify England, he is commemorated as a Saint by the Anglican Communion.

“O Sovereign Lord, you brought your servant Alfred to a troubled throne that he might establish peace in a ravaged land and revive learning and the arts among the people: Awake in us also a keen desire to increase our understanding while we are in this world, and an eager longing to reach that endless life where all will be made clear; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.”

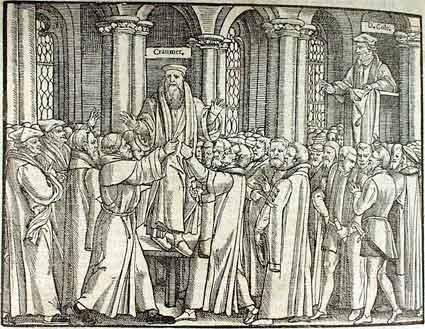

On March 21, 1556 Thomas Cranmer was executed in Oxford, after giving his final speech at St. Mary’s Church, Oxford. It was expected that Cranmer would recant and urge his fellow Protestants to return to the Roman Catholic faith. Cranmer, of course, repudiated the Pope and Roman Catholicism, and became a martyr. The images here are from Foxe’s Acts and Monuments which graphically described the Marian-era burnings for generations of Protestants to come.

As the 21st draws near, watch a short video below about the final speech. We’ll have some more Cranmer-related posts up over the next few weeks.

Merciful God, who through the work of Thomas Cranmer didst renew the worship of thy Church by restoring the language of the people, and through whose death didst reveal thy power in human weakness: Grant that by thy grace we may always worship thee in spirit and in truth; through Jesus Christ, our only Mediator and Advocate, who livest and reignest with thee and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

King Charles I (1600-1649) ascended to the English throne on March 27, 1625. Charles I was at odds with the Puritans in England at the time. He had married a French Catholic Princess named Henrietta Maria, and did not embrace Calvinism, as did the Puritans. Charles I had a more Arminian view of theology: he believed that people have a free will to embrace Christ. Like his Archbishop of Canterbury William Laud, he took a high view of church governance and worship, demanding compliance with the Book of Common Prayer and taking a traditional view of the importance of the sacraments. He was a strong believer in the episcopacy, bishops, which of course alienated him from the Puritans in Parliament, who believed in the Presbyterian form of government.

Almost immediately after becoming King, Charles I was at odds with Parliament. Within five months after his coronation he dissolved Parliament and would not call them into session for eleven years, from 1629 until 1641. This was called the “Period of Personal Rule.” There is no doubt he shared Laud’s assessment of Parliament, “that noise,” and was a strong believer in the divine right of kings.

Charles was able to extract revenue without the use of Parliament’s legislative power, but in 1640, faced with a dire need of funds to pay for the second “Bishops War” with Scotland. He reluctantly called Parliament back into session and in 1641 Parliament presented Charles with the Grand Remonstrance, a list of grievances against the King.

The situation continued to deteriorate and Charles left London in August 1642 and headed to Nottingham where he raised an army. Civil war had begun. Parliament remained in session and, dominated by Puritans, outlawed the Episcopacy. The Book of Common Prayer was made illegal in 1644. The prayer book was found to be “an offence to many of the Godly at home but also to the Reformed Churches abroad.”

By 1647 Charles had been defeated on the battlefield and he pretended to negotiate a settlement with Parliament. At the same time, though, he was trying to form an alliance with the Scots, promising that England would be Presbyterian for three years if the Scots invaded England. This “Second Civil War” was lost by the Royalists in 1648.

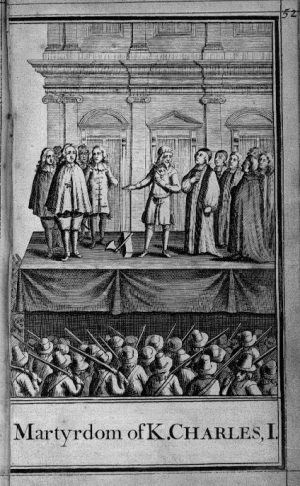

At that time, it was apparent that there would be no peace as long as Charles was alive. He was tried by Parliament for treason and blamed for the deaths in the two civil wars. Charles was asked to plead but refused, which was considered an admission of guilt. He was convicted in one week and 59 commissioners, all supporters of Parliament, signed his death warrant.

Charles I was executed in front of the banqueting hall at Whitehall Palace, London on January 30, 1649. When the executioner held up Charles’ severed head to the crowd, he did not say the traditional “behold the head of a traitor.” Immediately following the execution the crowd rushed the scaffold to get relics.

After the Restoration, where the monarchy was re-established in 1660, Charles was declared a martyr and saint by the Church of England in 1662. He would be the last person canonized by the English church. Those who signed the death warrant of Charles I, and there were 31 of the 59 living at the time, regretted their signatures: six of the commissioners were tried and hanged. Oliver Cromwell, the “Lord Protector” of England who died in 1658, was disinterred and hanged anyway, with his body made to face in the direction of Whitehall Palace.

A devotional cult was established in Charles’ name and he is considered an Anglican martyr, especially by Anglo Catholics. It is said that if Charles had been willing to abandon the church and give up the episcopacy he might have saved his throne and his life. Charles would not give to either demand, and as Gladstone said, “it was for the Church that Charles shed his blood on the scaffold.

Charles was removed as a saint from the calendar in 1859 but his feast day continues to be observed in the Church of England. The Society of King Charles the Martyr continues devotional activities in his memory, which can be found here.

Charles is commemorated in churches across England and his last word of “REMEMBER” can be found on statues. A hymn written to St. Charles contains this verse:

“For England’s Church, for England’s realm (Once thine in earthly sway), Lest storms our Ark should overwhelm, Saint Charles of England pray!”

In our previous post on this subject we talked about how the Episcopal Church managed to begin the lengthy process of rebuilding itself following the Revolutionary War. The church had lost a significant number of its members, around 40%, during the War and many of its clergy fled to Canada or returned to England. Where the old Church of England had been the established Church, such as Georgia and Virginia, colonial legislatures quickly dis-established the Church, causing a loss of assets. The Church had clearly seen better days.

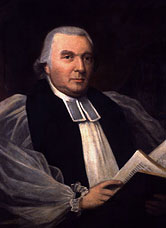

One question that the new Church began to ask itself is whether it should have bishops. Bishop William White, who we mentioned here, and others were convinced that the new Church which was to stand in place of the Church of England, should follow the traditions of the Church of England as closely as possible including a “superior order of clergy,” namely bishops. The new church, in fact, was named an “episcopal church” for that reason, the word “episcopal” being derived from the Greek episkopos which stands for “overseer.” Slowly, the name “Protestant Episcopal Church” began to stand out as the name for the new church to distinguish it from the Roman Catholic Church.

White, who wrote extensively about the role of the bishop in his brilliant essay, The Case of the Episcopal Churches Considered, argued for this “superior order,” but realized the idea would be unpopular with much of the laity. And for good reason. Many colonists or their ancestors left England due to religious persecution at the hands of English bishops and remembered the extensive civil powers that English bishops, who represented the Crown as well as the Church. America had just fought a war to rid themselves of royal tyranny. Why go back? As White put it, “there cannot be produced an instance of a layman in America, unless in the very infancy of the settlement, soliciting the introduction of a bishop.”

The answer, in White’s mind, was to create bishops who were devoid of any civil authority, elected by the clergy and laity, and who could be removed from office, or deprived, by those who elected them. A guiding principle for White was that those who empower the bishop can also remove the bishop.

Slowly, a general consensus emerged that the new church would have bishops. The next question would be, where do we get one from? Remember the colonies never had a bishop. The topic came up from time to time, but colonists feared the introduction of bishops would cause the same problems that they did in England, and resisted it. Other roadblocks to an American bishop included how to appoint a bishop, and what the duties and powers of a bishop would be in the colonies which were governed differently than the mother country. So there never was a bishop for the colonies, and now, following the Revolutionary War, English bishops would not consecrate an American as bishop due to the requirement of loyalty to the Crown, among other reasons. So, the prospect of a bishop looked fairly poor to White and others.

Samuel Seabury of Connecticut, a Church of England priest and royalist sympathizer during the Revolutionary War, was actually elected bishop by the developing church in Connecticut, and traveled to England in 1783 seeking consecration. Unable to swear allegiance to the Crown, he could not be consecrated. He traveled to Scotland where he was consecrated by three non-juring bishops of the Scottish Episcopal Church, who did not require an oath of allegiance to the Crown. Seabury returned to Connecticut and promptly organized the Episcopal Church of Connecticut.

Problem solved, right? Wrong! Seabury, while being the first bishop of the new Episcopal Church, was not recognized in some quarters for various reasons, including his pro-English stance during the Revolutionary War (he served part of the time as a Royal Army chaplain and even after the war received a small stipend from the English government), his Scottish consecration (remember the Scottish bishops left the Church of England during the non-juring schism), and the fact that he favored a “strong episcopacy” model, where lay persons had no role in governance.

The Second General Convention of the new Episcopal Church began to solve the problem when it elected William White and Samuel Provoost, rector of Trinity Church, New York City, as bishops in 1786. White and Provoost traveled to England in the same year and found a greater willingness on the part of English bishops, aided by a new law from Parliament that allowed them to consecrate Americans, to help the new church. White and Provoost were consecrated bishops by the Archbishops of Canterbury and York and the Bishop of Bath and Wells in 1787 and returned to the United States.

In return for their consecration, White and Provoost agreed not to consecrate bishops in America until three bishops had been consecrated by English bishops. James Madison was consecrated bishop in 1790 and returned to serve as Bishop of Virginia. The first bishop consecrated on American soil was Thomas Claggett, who was consecrated Bishop of Maryland in 1792 by White, Provoost, and Seabury.

In 1789 the Third General Convention met and after much compromise, agreed on the validity of Seabury’s episcopal orders and created a bi-cameral form of governance with a House of Bishops and House of Lay and Clerical Deputies. The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America was up and running with its own bishops, a new constitution, and an American Book of Common Prayer.

This was only the start, however. Much work remained to be done and it wasn’t until the early 1800’s that the new church began to experience solid growth. Its was, however, a uniquely American expression of what would be called one day, “Anglicanism.”

William Laud, 1573-1645, was Archbishop of Canterbury during the reign of King Charles I of England and regarded by many as an Anglican martyr. Appointed as Archbishop in 1633, Laud shared Charles I’s “high church” views of church governance by bishops and uniformity of worship according to the Book of Common Prayer. This was in sharp contrast to the Puritan factions in the Church of England at the time who took a more Calvinistic approach to worship and a Presbyterian form of government.

Note that “high church” at the time meant a high view of governance, such as bishops. It didn’t mean the “high church” that we equate today with a more Anglo-Catholic form of worship, namely incense, bells, chanting, and other liturgical elements. Laud did, however, bring back altars and communion rails after Puritan-leaning clergy removed them from their churches and demanded that clergy use the Book of Common Prayer for all worship services.

Laud thought that Puritanism was a threat to the episcopacy and to the Church as a whole and pursued Puritans in the infamous Star Chamber, where self-incrimination could be compelled and torture was frequently used. Those who were convicted of the crime of Sedition and Libel had their nose or an ear cut off and had “SL” branded on their cheek, for “Sedition and Libel.” Under Laud’s tenure the SL became known as the “Sign of Laud.”

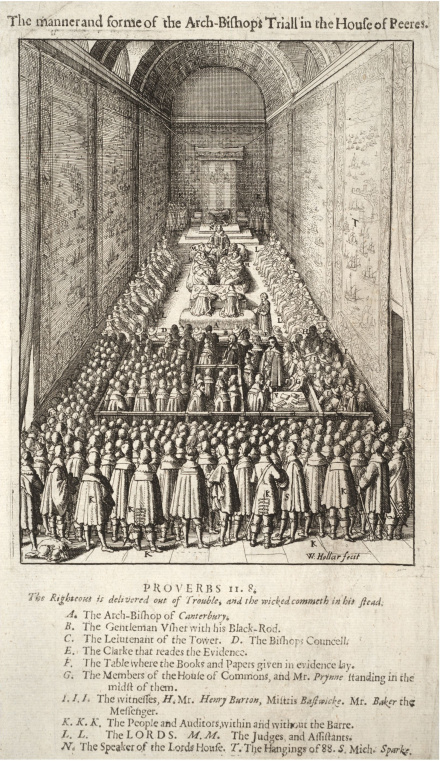

To say that Laud was unpopular was an understatement. A popular saying at the tim e was, “Give great praise to the Lord and little Laud to the Devil.” Finally in 1640 the Puritan forces in Parliament had him arrested. He was imprisoned for four years and finally tried, not by a court, but by Parliament (Charles I had control of the courts and the outcome would not have been satisfactory to his opponents.) A famous etching of the trial is reproduced below along with the quote from Proverbs, “The righteous are delivered from trouble and the wicked get into it instead.”

(Prov. 11:8) Laud was convicted by a bill of attainder by Parliament instead of a jury.

Laud was executed on Tower Hill on January 10, 1645. Laud preached his own funeral sermon on the scaffold, prefacing his comments with the observation that “this is an uncomfortable time to preach.”

His benefactor, Charles I, would, of course, meet the same end in 1649. Laud’s views of the episcopacy and other high church principles survived after the Restoration, and other Anglican divines known as “Laudians”, carried on his work for future generations of Anglicans.

The Reverend Lucius Waterman in 1912 summed up Laud’s contribution best when he observed that:

That we have our Prayer Book, our Altar, even our Episcopacy itself, we may, humanly speaking, thank Laud …… That our Articles have not a Genevan sense tied to them and are not an intolerable burden to the Church, is due to Laud. ….. . Laud saved the English Church …… The English Church in her Catholic aspect is a memorial to Laud.” (from here)

He continues, quoting Gladstone:

Laud as a Churchman has lasted. He lives to-day. His opponents have mostly disappeared from off the earth. They have left consequences, but no representatives. Laud has both.

From the 1979 BCP:

Keep us, O Lord, constant in faith and zealous in witness, that, like your servant William Laud, we may live in your fear, die in your favor, and rest in your peace; for the sake of Jesus Christ your Son our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen

In Parts I and II we examined the background events and players in the English Reformation that led up to the breach with Rome and the creation of the Church of England. In this post, we’ll examine the actual breach itself and look at some of the key players involved in these events.

In Part II we discussed how Cardinal Wolsey fell from favor with Henry VIII by failing to procure the King’s annulment. After Wolsey’s fall his secretary, Thomas Cromwell, began to emerge as Henry’s most trusted adviser and would eventually become Lord Chancellor (after the execution of Thomas More) and help lead the English Reformation.

Cromwell’s partner in these events was Thomas Cranmer, a priest and theologian from Cambridge who proposed that Henry’s case for annulment be put to leading intellectuals from the great universities of Europe. Henry had Cranmer travel to Rome in 1530 to argue his case personally.

The Parliament of 1529 was strongly anti-clerical and in 1530, urged on by Cromwell, began to take steps to establish the King’s authority over the English church. The entire English clergy (remember, they were Roman Catholic at the time) was charged with Praemunire, which, as we discussed in Part II, was an English legal doctrine that held you could not serve the King and a foreign master (i.e. the Pope) simultaneously. The clergy, led by then-Archbishop of Canterbury William Warham, agreed to a settlement with Henry in which they paid a significant fine and received a pardon. The Pardon of the Clergy also required the clergy to admit that Henry was the Supreme Head of the Church of England, “so far as the law of Christ allows.”

Parliament, urged on by Cromwell, continued to take action against the church and in 1532 passed the Supplication Against the Ordinaries, which was a list of grievances against the English church by parliament. Some of the grievances included the independent legislative powers of the church in such areas of marriage.

Warham, who was ailing at the time, settled this matter as well with a settlement known as the Submission of the Clergy, where the English church agreed to have its canons reviewed by the King, who could veto any legislation passed by the Convocation, which was the governing council of the church.

Shortly thereafter, Warham died and Henry VIII appointed Cranmer as Archbishop of Canterbury. Cranmer, who was traveling in Europe at the time, perhaps knew the challenges (or dangers) of working so closely with Henry, and tried not to respond to the letter as long as he could. In the end, however, he accepted the appointment and the Papal Bulls, or formal order, appointing him to the position arrived in England by March, 1533. Henry was so enthusiastic to have Cranmer as Archbishop that he paid for the bulls from his own funds (at that time the customary fee for a Papal Bull was the one year’s income from the benefices held by the office).

After Cranmer was consecrated Archbishop in March, 1532 Parliament continued to move against the Pope. They passed the Act in Conditional Restraint of Annates, which halted the payment for Papal Bulls for offices such as bishoprics (the money went to the Royal Treasury instead) and in 1533 passed the Act in Restraint of Appeals, which denied appeal to Rome in cases of marriage and other matters, and instead gave final authority in these matters to Henry’s archbishop, Thomas Cranmer.

Parliament acted again in 1534 and passed the Act of Supremacy which confirmed Henry’s title as the Supreme Head of the Church of England, effectively separating the church from the Pope. Opposing the Royal Supremacy was punishable by death.

After the Act in Conditional Restraint of Annates, Henry appealed to Cranmer regarding his marriage. Cranmer annulled Henry’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon in May, 1533 and validated Henry’s previously secret marriage to Anne Boelyn. On June 1, 1533 Cranmer crowned Anne as Queen of England. Pope Clement VII’s response was to excommunicate Henry, Anne, Cranmer and others unless Anne was repudiated. This, of course, did not occur and Anne, who was pregnant when she secretly married Henry, gave birth to the Princess Elizabeth on September 7, 1533. An excellent timeline of these legislative acts can be seen here.

The English Reformation had begun. The Church of England was free from Rome, but it wasn’t remotely Anglican and still very Catholic. Mass was still said in Latin, priests were supposed to be celibate, and the calendar of the saints was still followed.

What distinguishes this part of the English Reformation was that it wasn’t a reformation in terms of doctrine, but rather, some excellent lawyering on the part of Cromwell and his allies in the Reformation Parliament. It was a reformation by statute, not from changed doctrine.

The emergence of protestant ideas would come in the next phase, from committed Reformers such as Cranmer, Cromwell, and others. But with the King a fairly contended Catholic, how far would they go? We’ll address that in our next post on the English Reformation.

Ask most people in an Episcopal congregation about the beginnings of the Episcopal Church after the Revolutionary War and they’ll tell you that “it was formed out of the Church of England.” Maybe in confirmation class some years ago you recall learning about Samuel Seabury, Bishop of Connecticut, who was the first Episcopalian bishop in America. And the rest is, well, church history.

Picture yourself an American member of the colonial Church of England (COE) during or after the Revolutionary War. Your church was part of the royal government, the same government that people were fighting against. Perhaps you felt more allegiance to the Crown than your fellow colonists. After all, the Church of England in the United States (remember “Anglican” wasn’t a term in common use until the 19th century) attracted members of the merchant class, civil servants, royal governors, and others with strong ties to England.

If you left during the Revolution to go to Canada or return to England you weren’t alone. About 40% of Anglicans did. For those who stayed on after the war, their church was a shadow of its former self. Where the COE was the established (government-subsidized) church, such as the southern colonies and parts of New York, the church was quickly dis-established and lands sold off. Clergy, who took an oath of loyalty to the King, were caught in a dilemma: do you remain faithful to your ordination vows and support the King or side with the colonists who were part of the Revolution?

All these and more problems faced those clergy and laity who remained in the church after the Revolution. To begin with, the church had no name. You couldn’t really call it the COE, since the colonies were free. There were no bishops in the colonies before the Revolution (there never were, as clergy traveled to England for ordination before the War) and there was no mechanism to consecrate any new ones. Church assets and property was lost to disestablishment and there were 40% fewer members to support the church.

The old COE brought its liturgical tradition with it from England, and used the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. What liturgical tradition would the new church use? How could the church use a prayer book that contained prayers for the King?

These questions were on the minds of soon-to-be-Episcopalians in the colonies.

A Pennsylvania rector, the Rev. William White, of Christ and St. Peter’s Churches in Philadelphia, stepped up and proposed several solutions including some thoughts on bishops, tradition, and how this new church should be governed. During that time a name for the new church was proposed as well.

The Rev. White was born in Pennsylvania in 1742 and ordained in London in 1770. He returned to Philadelphia in 1772 and served as the assistant at Christ Church and later became rector of both Christ Church and its sister church, St. Peter’s. While was sympathetic to the Revolution and served as chaplain to the Continental Congress (he would eventually become the United States Senate Chaplain).

In 1782 White wrote The Case of the Episcopal Churches in the United States Considered (available from here) where he addressed a number of issues. He began by acknowledging the spiritual connection with the COE but noted that the Revolutionary War dissolved any allegiance to it. White’s masterful argument for the development of an American church modeled on some features of the COE was based on very Anglican principles. The frotispiece of the work quotes the great English theologian Hooker:

To make new articles of faith and doctrine, no man thinketh it lawful; new laws of government, what commonwealth or church is there which maketh not at one time or another?

White continues his argument by noting that the authority for a national church to set its own tradition is found in the Articles of Religion, namely Article 35, which states:

Every particular or national Church hath authority to ordain, change, and abolish, Ceremonies or Rite of the Church ordained only by man’s authority, so that all things may be done to edifying.

It was, therefore, not only the right thing to do, but a very Anglican thing to do to incorporate the tradition of the COE into the new church without being governed by or swearing allegiance to it.

So where did the name Episcopal come from? The word episcopal is derived from the Greek episkopos and means overseer. The term “episcopal” was used to mean bishops, and to distinguish the Church of England model of governance, i.e. bishops, from other Protestant models of governance that did not have an episcopal form of governance, such as the Presbyterians or the Puritans. “Protestant Episcopal” was used in the colonies around 1780 to differentiate the new church from Roman Catholic churches, especially in the former Roman Catholic colony of Maryland. (Holmes, A Brief History of the Episcopal Church, page 50)

The concept of bishops was a contentious one for the colonies, as bishops implied the authority of the King, and, after all, isn’t that why there was a revolution? If there was never a Church of England bishop in the colonies before the war, why start now?

In the next post on this subject we’ll talk more about bishops, and how the new church eventually got some.

From Kings College Chapel, Cambridge. The 2013 Lessons and Carols Service will be broadcast by BBC Radio on Christmas Eve. Find out more about the service and a link to BBC Radio here.

Recent Comments