Here are the three remaining parts of Burning Convictions, Parts IV through VI.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSoRcFEWGpc

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y4B8LhFXDDY&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eCUfk_7ULlI&feature=related

The BBC’s A History of Britain episode on the English Reformation continues with Simon Schama’s Burning Convictions, Parts II and III:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NIXRrh3eUIA&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ui9aHLlYjsU&feature=related

DG2B2XSDQJR4

From the BBC’s A History of Britain. Simon Schama takes us through the English Reformation with some great video, in an episode entitled “Burning Convictions.” Part 1 of 6 is below.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tq6e6V3btp8

In Part I we set the stage for the beginnings of the English Reformation. Now its time to look at what the religious climate was in England immediately before the breach with Rome and the beginnings of the Church of England.

The Roman Catholic Church in early 16th century England was very much like the Catholic Church in the remainder of Europe. Mass was said in Latin, the Bible was not available to lay people, priests did not marry and a person could receive forgiveness of sins by the purchase of indulgences from the Church. Masses were said for the dead to allow them to escape purgatory and priests were paid from the estate of the deceased to say Mass regularly on their behalf.

The Reformation on the continent did not go unnoticed in England, however. As the laity began to become more educated, reforming ideas from Europe became to be regularly discussed in England as well. The printing press proved to be a major catalyst in the Reformation, both in England and the continent, especially considering that you didn’t need to know Latin or Greek, or be a university scholar or in Holy Orders, to be able to read and discuss religious issues.

By 1521 Lutheran books were coming into England and people were discussing religious issues. Luther, a German monk and New Testament scholar, challenged the Roman Catholic Church’s views on salvation, indulgences, and the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, which holds that the bread and wine consecrated by the priest during Mass actually becomes the physical body and blood of Christ.

The reaction to this by the English Church and the Crown was swift. Bishop John Fisher, along with other English bishops, led the charge against Luther’s works and a ceremonial burning of Luther’s works was held at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London in 1521.

Other notable English clergy were involved in discussing Luther’s ideas, including a group of Cambridge scholars many of whom would become first generation English reformers (and martyrs) including William Tyndale, Thomas Parker, Hugh Latimer, Thomas Cranmer, and Nicholas Ridley.

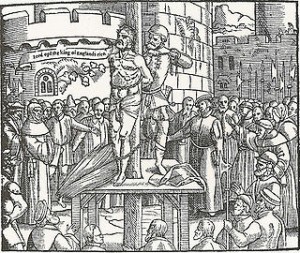

William Tyndale, a committed reformer, translated the Bible into English. Fearing for his safety he traveled to Germany and met Luther. He translation of the New Testament appeared in England in the late 1520’s, and he produced other writings that discussed the supremacy of Scripture over everything else. He was eventually tracked down by English agents in Brussels, and in 1536 condemned to death for heresy. He was strangled to death and then burned on the stake, as depicted below in Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, which chronicled the martyrs of the English Reformation. Tyndale’s final words were, “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes.”

Henry VIII’s response to Lutheran ideas was similar to that of the bishops. Henry wrote a response to Luther, opposing Lutheran doctrine and for the supremacy of the Pope. For his efforts, he was rewarded with the title of “Defender of the Faith” by the Pope, a title that English monarchs carry to this day.

If Luther’s ideas gave some in England reason for thought, the actions of the English clergy gave rise to strong feelings of anti-clericalism. The poster child for anticlericalism at the time was Henry’s chancellor, Cardinal Wolsey. Wolsey was held multiple titles including Cardinal, Archbishop of York, and a number of other bishoprics, which was not uncommon at the time. Fabulously wealthy, he built Hampton Court Palace (which he would later give to Henry VIII in a desperate attempt to save himself from being charged with treason-it didn’t work), and endowed a college at Oxford. Like many of the clergy at the time he had a mistress and several illegitimate children

Wolsey, who arose from humble beginnings, was given significant power by Henry VIII for handling the day to day business of the monarchy. Wolsey also arranged to be appointed a papal legate, which meant he acted in the name of the Pope in England. His significant power and wealth caused resentment among other bishops and members of Henry’s court, so much that once he failed to please the King, his downfall was assured.

That downfall stemmed from Henry’s attempts to get an annulment from his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. Remember that by 1525 Catherine had failed to produce a male heir for Henry and Henry’s attentions were focused on Anne Boleyn. Wolsey tried to intervene on Henry’s behalf with Pope Clement to grant an annulment, but Clement would not overrule the dispensation that had been given to Henry by then-Pope Julius. Clement’s refusal to grant an annulment was undoubtedly influenced by the fact that Catherine of Aragon’s uncle was Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, who actually attacked Rome in 1527 and kept Pope Clement VII under house arrest for a while.

By 1527 Henry had decided to marry Anne and began annulment proceedings. Clement sent another cardinal and papal legate, Cardinal Campeggio, who presided with Wolsey inannulment hearings inn England in 1528. Unfortunately, for Wolsey, Henry did not get the result he wanted, an annulment, and the case was remanded to Rome for a decision by the Pope. Given the situation with Charles V, it was obvious that the result was not going to be good for Henry.

Wolsey’s standing with Henry was significantly diminished after the case was sent back to Rome, especially after Anne and her supporters (who were pro-Reformation) at Court convinced Henry that Wolsey was putting the interests of the Church over Henry’s. Wolsey was deprived of the Chancellor’s office and forced to return to being Archbishop of York, the second-ranking primate in England (the Archbishop of Canterbury is first), and actually had to go to York, where he had never been before, although he was Archbishop (the requirement for Bishops to reside in their seas was one product of the Reformation). However this wasn’t enough for the anticlerical Reform-minded activists at Court, and Wolsey was eventually was charged with treason. He was charged under an ancient common law principle that it was illegal to serve another monarch (the Pope) at the expense of the King, and brought to Court under a writ of praemunire. Apparently, all of Wolsey’s actions as papal legate were illegal! Who knew?

Wolsey died in 1530 enroute to the Tower of London of natural causes and never faced the executioner. His final words included, “If I had served God as diligently as I have done the King, he would not have given me over in my grey hairs.”

At Court, Wolsey was gone and there was a strong reforming influence led by Anne and her supporters. Henry was determined to get his marriage to Catherine overturned, however, and began to take steps to assume more control of the English church. While Reforming principles were on the minds of many at Court, Henry remained a fairly content Catholic in matters of doctrine.

So, perhaps, maybe it was really all about Anne. In Henry’s mind it probably was. In the next post, we’ll examine the actual breach with Rome and learn about the key players involved, most of whom were committed reformers, and how they used the breach as an opportunity to bring reforming principles to England.

C.S. Lewis is the greatest Anglican apologist of the 20th century. C.S. Lewis was born in Ireland in 1898. His mother died when he was nine, and at age fifteen he became an atheist. Lewis eventually became a professor of English Literature at Oxford and in 1931 converted to Christianity. He wrote a number of influential Christian works including Mere Christianity, The Screwtape Letters, and The Great Divorce. He also wrote the famed children’s series The Chronicles of Narnia.

C.S. Lewis is the greatest Anglican apologist of the 20th century. C.S. Lewis was born in Ireland in 1898. His mother died when he was nine, and at age fifteen he became an atheist. Lewis eventually became a professor of English Literature at Oxford and in 1931 converted to Christianity. He wrote a number of influential Christian works including Mere Christianity, The Screwtape Letters, and The Great Divorce. He also wrote the famed children’s series The Chronicles of Narnia.

While C.S. Lewis was a member of the Church of England, he was not specifically an Anglican apologist. In Mere Christianity he writes of Christianity being a hall, out of which open several rooms, namely different understandings of Christianity. Lewis saw his role as bringing people from outside into the hallway, “If I can bring anyone into that hall I shall have done what I attempted.” (Mere Christianity, xv) Lewis’ approach to apologetics, however, strikes a particularly Anglican tone. He presents a theory for our consideration and if it helps our understanding of complex theological matters, fine. If not, we are free to consider something else. Lewis’ apologetic is fluid without sacrificing core belief.

Lewis died 47 years ago today, and his Feast Day is celebrated today in the Episcopal Church. From the 1979 BCP:

O God of searing truth and surpassing beauty, we give you thanks for Clive Staples Lewis, whose sanctified imagination lights fires of faith in young and old alike. Surprise us also with your joy and draw us into that new and abundant life which is ours in Christ Jesus, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever. Amen.

We Anglicans know the abbreviated version. How many times have we heard in casual conversation, Christian education programs, or elsewhere the short version of how Anglicanism came into being. It goes something like this “Henry VIII wanted a divorce from his wife so he could marry Anne Boleyn and when the Pope wouldn’t give him one he started the Church of England.” Remember that the final result, the separation of the English church from Rome wasn’t remotely “Anglican” in the sense we know it today. It wasn’t even the Church of England. That would come much later.

While Henry’s marital woes being the cause of the breach with Rome does have some truth to it, there’s a lot more to the story than just an expedient way to get a new Queen. In the next few posts we’re going to take a look at what led up to the separation between England and the Catholic Church, the influence of the Reformation on the Continent, the various players involved, and a whole lot more information about how the English Church came about.

Events of the Early 16th Century: Henry VII, Prince Arthur, Catherine and the Pope

Henry VIII became king with his father, Henry VII, died in 1509, at the age of eighteen. Henry VII won the throne in the War of the Roses in 1485. His successor was to be his eldest son, Arthur, however Arthur died in 1502. Arthur was married to Catherine of Aragon, daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain. The marriage was arranged to forge an alliance between England and Spain. In order to preserve the alliance, Henry VIII married Catherine of Aragon. Before Henry could marry Catherine a dispensation had to be obtained from the Pope, Julius II, which was done in 1503.

The dispensation itself is important as it would become the basis of Henry’s argument for an annulment of his marriage to Catherine. Julius II granted the dispensation on the grounds that Arthur and Catherine had only been married for a short period of time, three months, and that the marriage was never consummated. If this appears to be shaky ground, remember that the Vatican at the time derived a significant income stream from high level dispensations such as this and international politics played a significant role in this as well.

Henry and Catherine were married in 1509, shortly after Henry’s accession to the throne. She and Henry had six children, but only one, Mary Tudor, later Queen Mary of England, would survive to adulthood.

The lack of a male heir worried Henry, and, once again, this would become part of his case for an annulment of his marriage to Catherine. In years to come, Henry would rely on two verses of Leviticus for the Scriptural basis of his annulment namely, “thou shalt not uncover the nakedness of thy brother’s wife: it [is] thy brother’s nakedness,” (Lev 18:16) and “And if a man shall take his brother’s wife, it [is] an unclean thing: he hath uncovered his brother’s nakedness; they shall be childless.” (Lev. 20:21, both KJV)

So now the stage is set. We have Henry VIII, concerned about a male heir, and Catherine of Aragon, a devout Roman Catholic who cannot produce one, who also happens to be five years older than the King. These are only two of the players in the story. The next area to explore in early sixteenth century England is what was happening in the English church at the time, and see why it was fertile ground for a reformation, although that wasn’t exactly what Henry had in mind.

The English Reformation continues here on the blog. See Part II

St. Hilda of Whitby (614-680), whose Feast Day is November 18 in the Episcopal Church (November 17 in others) was the Abbess of the famed Whitby Abbey, originally known as the monastery Streonshalh, location of the Synod of Whitby in 684. Hilda’s contributions go deeper than hosting the Synod, though. Hilda was born to nobility, the daughter of Hereic, nephew to King Edwin of Northumbria. Hilda, along with Edwin and other members of his court, were baptized on Easter Day 627 by the bishop Paulinus, who accompanied Augustine on the Gregorian Mission to England.

When Hilda was about thirty three years old, she had answered the call to become a nun and had originally planned to live in a monastery in Gaul. The Bishop (later saint) Aidan of Lindisframe called her back to Northumbria and had her establish a monastery on the banks of the River Wear, becoming the first nun in Northumbria.

Hilda lived at the monastery until 657 when she established the monastery at what is now known as Whitby. The strict monastic rule was followed there and soon the monastery became known throughout the land. Kings, princes and ordinary folk came to Hilda for “her advice in their difficulties,” according to Bede. A monastery for men was also established at Whitby and five monks from that monastery became bishops.

The Synod of Whitby, which was held in 684, is significant for the decision of King Oswy, who convened the synod, to adopt, among other things, the Roman method for calculating the day of Easter, and to bring Northumbrian Christianity more in line with Roman traditions.

Hilda lived until the year 680. For some months before her death she was stricken with a fever, and Bede writes that when she died, a sister of the monastery saw her soul being taken to heaven in the company of angels. Her reputation for prudence, faith and devotion to the monastic way of life survives to this day.

The Collect for the Feast of St. Hilda (BCP, 1979):

O God of peace, by whose grace the abbess Hilda was endowed with gifts of justice, prudence, and strength to rule as a wise mother over the nuns and monks of her household, and to become a trusted and reconciling friend to the leaders of the Church: Give us the grace to recognize and accept the varied gifts you bestow on men and women, that our common life may be enriched and your gracious will be done; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever, Amen.

Welcome to the Anglican History Blog. As you may know, there is no shortage of blogs that comment on the current state of the Episcopal Church (TEC), Church of England (COE) and other members of the Anglican Communion. This blog is something different. Instead of focusing on the current state of affairs, we want to examine the rich history of Anglicanism, with the hopes of finding out how and why we came to where we are today.

Feel free to comment on these posts and share your insights. Much can be learned from our past and we look forward to the discussion.

Recent Comments