We Anglicans know the abbreviated version. How many times have we heard in casual conversation, Christian education programs, or elsewhere the short version of how Anglicanism came into being. It goes something like this “Henry VIII wanted a divorce from his wife so he could marry Anne Boleyn and when the Pope wouldn’t give him one he started the Church of England.” Remember that the final result, the separation of the English church from Rome wasn’t remotely “Anglican” in the sense we know it today. It wasn’t even the Church of England. That would come much later.

While Henry’s marital woes being the cause of the breach with Rome does have some truth to it, there’s a lot more to the story than just an expedient way to get a new Queen. In the next few posts we’re going to take a look at what led up to the separation between England and the Catholic Church, the influence of the Reformation on the Continent, the various players involved, and a whole lot more information about how the English Church came about.

Events of the Early 16th Century: Henry VII, Prince Arthur, Catherine and the Pope

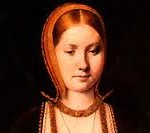

Henry VIII became king with his father, Henry VII, died in 1509, at the age of eighteen. Henry VII won the throne in the War of the Roses in 1485. His successor was to be his eldest son, Arthur, however Arthur died in 1502. Arthur was married to Catherine of Aragon, daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain. The marriage was arranged to forge an alliance between England and Spain. In order to preserve the alliance, Henry VIII married Catherine of Aragon. Before Henry could marry Catherine a dispensation had to be obtained from the Pope, Julius II, which was done in 1503.

The dispensation itself is important as it would become the basis of Henry’s argument for an annulment of his marriage to Catherine. Julius II granted the dispensation on the grounds that Arthur and Catherine had only been married for a short period of time, three months, and that the marriage was never consummated. If this appears to be shaky ground, remember that the Vatican at the time derived a significant income stream from high level dispensations such as this and international politics played a significant role in this as well.

Henry and Catherine were married in 1509, shortly after Henry’s accession to the throne. She and Henry had six children, but only one, Mary Tudor, later Queen Mary of England, would survive to adulthood.

The lack of a male heir worried Henry, and, once again, this would become part of his case for an annulment of his marriage to Catherine. In years to come, Henry would rely on two verses of Leviticus for the Scriptural basis of his annulment namely, “thou shalt not uncover the nakedness of thy brother’s wife: it [is] thy brother’s nakedness,” (Lev 18:16) and “And if a man shall take his brother’s wife, it [is] an unclean thing: he hath uncovered his brother’s nakedness; they shall be childless.” (Lev. 20:21, both KJV)

So now the stage is set. We have Henry VIII, concerned about a male heir, and Catherine of Aragon, a devout Roman Catholic who cannot produce one, who also happens to be five years older than the King. These are only two of the players in the story. The next area to explore in early sixteenth century England is what was happening in the English church at the time, and see why it was fertile ground for a reformation, although that wasn’t exactly what Henry had in mind.

The English Reformation continues here on the blog. See Part II

Recent Comments