One month ago The Most Reverend Justin Welby was enthroned at the 105th Archbishop of Canterbury. If you missed his enthronement service you can watch it here. So here’s a good opportunity to go back to the sixth century and take a look at the first Archbishop of Canterbury, St. Augustine, the mission to England, and how that helped give us the English church as we know it.

Part I-The Missionary Journey

The idea for a missionary trip to Britain began with Pope Gregory the Great (590-604). Before Gregory the Great began pope in 590 he had encountered Anglian slave boys being being sold on the open market in Rome around 586. Tradition has it that Gregory was so moved by the plight of these boys that he purchased them, had them baptized and then educated so that they could eventually return to England as missionaries.

Its important to understand the religious landscape of England at the time. The invasions of the Anglos and the Saxons earlier in the fourth century had forced Roman Christians living in England to abandon Christianity in favor of the paganism of their invaders or flee westward into Wales. While there was evidence that some Christians did, in fact, remain in eastern Britain, those Christians, according to the Venerable Bede, the great historian of the early English church.

Gregory’s concern for the spiritual welfare of the English people continued to grow and, as Bede tells is, “he put in hand his long-cherished project.” He secured the support of a number of Christian monarchs for the mission including (now a saint) Queen Bertha, a Frankish Christian and the wife of (now also a saint) King Aethelbert of Kent, who at the time was a pagan.

In 596 Gregory the Great selected Augustine, who was a monk at the same monastery

on Coelian Hill where Gregory had served before becoming Pope, to lead the mission to England. As Augustine and his party traveled through Gaul they heard stories of the savagery of the English people and considered returning home. Pope Gregory wrote to Augustine advising him to continue telling him “the greater the labor, the greater will be your eternal reward.”

Part II-Landing in Kent

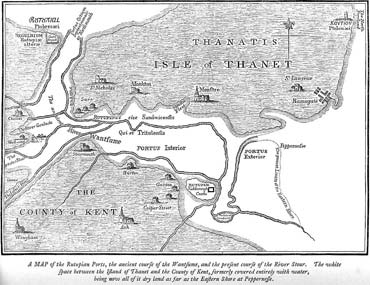

Map of the Isle of Thanet in medieval times. The channel between the isle and mainland closed off by 1500 making Thanet no longer an island.

Augustine and his party landed on the Isle of Thanet off the coast of Kent in early 597. King Aethelbert sent greetings to them and provided them with necessaries but did ask them to remain on the isle until he could have an audience with them. During their audience with Aethelbert, which was held out of doors for fear of the monks placing a magic spell upon the King, the monks sang a litany and preached to him. Aethlebert, according to Bede, told the monks that he could not “abandon the age-old beliefs that I have held along with the whole English nation.” He allowed the monks to come to the mainland and gave them a dwelling place.

Part III-The Conversion of England

Aethelbert would quickly convert to Christianity but did not require it of his subjects as he thought “the service of Christ must be accepted freely and not under compulsion.” Augustine became a bishop in the fall of 597 A.D. and during Christmas of 597 he and his fellow missionaries baptized 10,000 converts. Once Christianity had been established in Kent, Gregory instructed Augustine to send a bishop to York who would consecrate twelve more bishops and become an archbishop. The new archbishop would, however, remain subject to the authority of Augustine. Augustine also consecrated bishops of London and Rochester in 604 and it was planned that the Archbishop of Canterbury would move to London and this would become the primatial see, but this never occurred.

Augustine died in 604 and was buried outside the church of the Abbey of Saints Peter and Paul (now known as St. Augustine’s Abbey) as the church itself was not yet finished. Miracles were attributed to him and he was canonized a saint. His shrine, lost in the English Reformation, is now located in St. Augustine’s Ramsgate, a church of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Southwark, notable for its design by and burial place of the Victorian church architect Augustus Welby Pugin.

An important feature of Augustine’s episcopacy was how he (and Pope Gregory) handled local religious customs. When Augustine wrote to Gregory and asked him why customs differed in various churches, Gregory answered that Augustine should “select from each of the church whatever things are “devout, religious and right,” and to “let the minds of the English people grow accustomed” to them. Pagan temples were not destroyed, they were blessed, altars set up, and relics deposited there for use during celebration of the saints days which replaced pagan festivals.

Rivalry between Augustine and bishops from other parts of Britain resulted in Augustine not being able to unify the entire English church. While it would take centuries more to unify the church in England, Augustine’s and Gregory’s gift to us was the beginning of a change in the culture of Britain and a huge step forward in the development of the English church.

Recent Comments