In our previous post on this subject we talked about how the Episcopal Church managed to begin the lengthy process of rebuilding itself following the Revolutionary War. The church had lost a significant number of its members, around 40%, during the War and many of its clergy fled to Canada or returned to England. Where the old Church of England had been the established Church, such as Georgia and Virginia, colonial legislatures quickly dis-established the Church, causing a loss of assets. The Church had clearly seen better days.

One question that the new Church began to ask itself is whether it should have bishops. Bishop William White, who we mentioned here, and others were convinced that the new Church which was to stand in place of the Church of England, should follow the traditions of the Church of England as closely as possible including a “superior order of clergy,” namely bishops. The new church, in fact, was named an “episcopal church” for that reason, the word “episcopal” being derived from the Greek episkopos which stands for “overseer.” Slowly, the name “Protestant Episcopal Church” began to stand out as the name for the new church to distinguish it from the Roman Catholic Church.

White, who wrote extensively about the role of the bishop in his brilliant essay, The Case of the Episcopal Churches Considered, argued for this “superior order,” but realized the idea would be unpopular with much of the laity. And for good reason. Many colonists or their ancestors left England due to religious persecution at the hands of English bishops and remembered the extensive civil powers that English bishops, who represented the Crown as well as the Church. America had just fought a war to rid themselves of royal tyranny. Why go back? As White put it, “there cannot be produced an instance of a layman in America, unless in the very infancy of the settlement, soliciting the introduction of a bishop.”

The answer, in White’s mind, was to create bishops who were devoid of any civil authority, elected by the clergy and laity, and who could be removed from office, or deprived, by those who elected them. A guiding principle for White was that those who empower the bishop can also remove the bishop.

Slowly, a general consensus emerged that the new church would have bishops. The next question would be, where do we get one from? Remember the colonies never had a bishop. The topic came up from time to time, but colonists feared the introduction of bishops would cause the same problems that they did in England, and resisted it. Other roadblocks to an American bishop included how to appoint a bishop, and what the duties and powers of a bishop would be in the colonies which were governed differently than the mother country. So there never was a bishop for the colonies, and now, following the Revolutionary War, English bishops would not consecrate an American as bishop due to the requirement of loyalty to the Crown, among other reasons. So, the prospect of a bishop looked fairly poor to White and others.

Samuel Seabury of Connecticut, a Church of England priest and royalist sympathizer during the Revolutionary War, was actually elected bishop by the developing church in Connecticut, and traveled to England in 1783 seeking consecration. Unable to swear allegiance to the Crown, he could not be consecrated. He traveled to Scotland where he was consecrated by three non-juring bishops of the Scottish Episcopal Church, who did not require an oath of allegiance to the Crown. Seabury returned to Connecticut and promptly organized the Episcopal Church of Connecticut.

Problem solved, right? Wrong! Seabury, while being the first bishop of the new Episcopal Church, was not recognized in some quarters for various reasons, including his pro-English stance during the Revolutionary War (he served part of the time as a Royal Army chaplain and even after the war received a small stipend from the English government), his Scottish consecration (remember the Scottish bishops left the Church of England during the non-juring schism), and the fact that he favored a “strong episcopacy” model, where lay persons had no role in governance.

The Second General Convention of the new Episcopal Church began to solve the problem when it elected William White and Samuel Provoost, rector of Trinity Church, New York City, as bishops in 1786. White and Provoost traveled to England in the same year and found a greater willingness on the part of English bishops, aided by a new law from Parliament that allowed them to consecrate Americans, to help the new church. White and Provoost were consecrated bishops by the Archbishops of Canterbury and York and the Bishop of Bath and Wells in 1787 and returned to the United States.

In return for their consecration, White and Provoost agreed not to consecrate bishops in America until three bishops had been consecrated by English bishops. James Madison was consecrated bishop in 1790 and returned to serve as Bishop of Virginia. The first bishop consecrated on American soil was Thomas Claggett, who was consecrated Bishop of Maryland in 1792 by White, Provoost, and Seabury.

In 1789 the Third General Convention met and after much compromise, agreed on the validity of Seabury’s episcopal orders and created a bi-cameral form of governance with a House of Bishops and House of Lay and Clerical Deputies. The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America was up and running with its own bishops, a new constitution, and an American Book of Common Prayer.

This was only the start, however. Much work remained to be done and it wasn’t until the early 1800’s that the new church began to experience solid growth. Its was, however, a uniquely American expression of what would be called one day, “Anglicanism.”

Ask most people in an Episcopal congregation about the beginnings of the Episcopal Church after the Revolutionary War and they’ll tell you that “it was formed out of the Church of England.” Maybe in confirmation class some years ago you recall learning about Samuel Seabury, Bishop of Connecticut, who was the first Episcopalian bishop in America. And the rest is, well, church history.

Picture yourself an American member of the colonial Church of England (COE) during or after the Revolutionary War. Your church was part of the royal government, the same government that people were fighting against. Perhaps you felt more allegiance to the Crown than your fellow colonists. After all, the Church of England in the United States (remember “Anglican” wasn’t a term in common use until the 19th century) attracted members of the merchant class, civil servants, royal governors, and others with strong ties to England.

If you left during the Revolution to go to Canada or return to England you weren’t alone. About 40% of Anglicans did. For those who stayed on after the war, their church was a shadow of its former self. Where the COE was the established (government-subsidized) church, such as the southern colonies and parts of New York, the church was quickly dis-established and lands sold off. Clergy, who took an oath of loyalty to the King, were caught in a dilemma: do you remain faithful to your ordination vows and support the King or side with the colonists who were part of the Revolution?

All these and more problems faced those clergy and laity who remained in the church after the Revolution. To begin with, the church had no name. You couldn’t really call it the COE, since the colonies were free. There were no bishops in the colonies before the Revolution (there never were, as clergy traveled to England for ordination before the War) and there was no mechanism to consecrate any new ones. Church assets and property was lost to disestablishment and there were 40% fewer members to support the church.

The old COE brought its liturgical tradition with it from England, and used the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. What liturgical tradition would the new church use? How could the church use a prayer book that contained prayers for the King?

These questions were on the minds of soon-to-be-Episcopalians in the colonies.

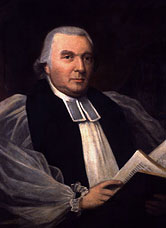

A Pennsylvania rector, the Rev. William White, of Christ and St. Peter’s Churches in Philadelphia, stepped up and proposed several solutions including some thoughts on bishops, tradition, and how this new church should be governed. During that time a name for the new church was proposed as well.

The Rev. White was born in Pennsylvania in 1742 and ordained in London in 1770. He returned to Philadelphia in 1772 and served as the assistant at Christ Church and later became rector of both Christ Church and its sister church, St. Peter’s. While was sympathetic to the Revolution and served as chaplain to the Continental Congress (he would eventually become the United States Senate Chaplain).

In 1782 White wrote The Case of the Episcopal Churches in the United States Considered (available from here) where he addressed a number of issues. He began by acknowledging the spiritual connection with the COE but noted that the Revolutionary War dissolved any allegiance to it. White’s masterful argument for the development of an American church modeled on some features of the COE was based on very Anglican principles. The frotispiece of the work quotes the great English theologian Hooker:

To make new articles of faith and doctrine, no man thinketh it lawful; new laws of government, what commonwealth or church is there which maketh not at one time or another?

White continues his argument by noting that the authority for a national church to set its own tradition is found in the Articles of Religion, namely Article 35, which states:

Every particular or national Church hath authority to ordain, change, and abolish, Ceremonies or Rite of the Church ordained only by man’s authority, so that all things may be done to edifying.

It was, therefore, not only the right thing to do, but a very Anglican thing to do to incorporate the tradition of the COE into the new church without being governed by or swearing allegiance to it.

So where did the name Episcopal come from? The word episcopal is derived from the Greek episkopos and means overseer. The term “episcopal” was used to mean bishops, and to distinguish the Church of England model of governance, i.e. bishops, from other Protestant models of governance that did not have an episcopal form of governance, such as the Presbyterians or the Puritans. “Protestant Episcopal” was used in the colonies around 1780 to differentiate the new church from Roman Catholic churches, especially in the former Roman Catholic colony of Maryland. (Holmes, A Brief History of the Episcopal Church, page 50)

The concept of bishops was a contentious one for the colonies, as bishops implied the authority of the King, and, after all, isn’t that why there was a revolution? If there was never a Church of England bishop in the colonies before the war, why start now?

In the next post on this subject we’ll talk more about bishops, and how the new church eventually got some.

Recent Comments