King Charles I (1600-1649) ascended to the English throne on March 27, 1625. Charles I was at odds with the Puritans in England at the time. He had married a French Catholic Princess named Henrietta Maria, and did not embrace Calvinism, as did the Puritans. Charles I had a more Arminian view of theology: he believed that people have a free will to embrace Christ. Like his Archbishop of Canterbury William Laud, he took a high view of church governance and worship, demanding compliance with the Book of Common Prayer and taking a traditional view of the importance of the sacraments. He was a strong believer in the episcopacy, bishops, which of course alienated him from the Puritans in Parliament, who believed in the Presbyterian form of government.

Almost immediately after becoming King, Charles I was at odds with Parliament. Within five months after his coronation he dissolved Parliament and would not call them into session for eleven years, from 1629 until 1641. This was called the “Period of Personal Rule.” There is no doubt he shared Laud’s assessment of Parliament, “that noise,” and was a strong believer in the divine right of kings.

Charles was able to extract revenue without the use of Parliament’s legislative power, but in 1640, faced with a dire need of funds to pay for the second “Bishops War” with Scotland. He reluctantly called Parliament back into session and in 1641 Parliament presented Charles with the Grand Remonstrance, a list of grievances against the King.

The situation continued to deteriorate and Charles left London in August 1642 and headed to Nottingham where he raised an army. Civil war had begun. Parliament remained in session and, dominated by Puritans, outlawed the Episcopacy. The Book of Common Prayer was made illegal in 1644. The prayer book was found to be “an offence to many of the Godly at home but also to the Reformed Churches abroad.”

By 1647 Charles had been defeated on the battlefield and he pretended to negotiate a settlement with Parliament. At the same time, though, he was trying to form an alliance with the Scots, promising that England would be Presbyterian for three years if the Scots invaded England. This “Second Civil War” was lost by the Royalists in 1648.

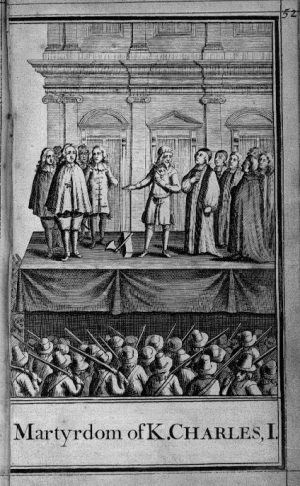

At that time, it was apparent that there would be no peace as long as Charles was alive. He was tried by Parliament for treason and blamed for the deaths in the two civil wars. Charles was asked to plead but refused, which was considered an admission of guilt. He was convicted in one week and 59 commissioners, all supporters of Parliament, signed his death warrant.

Charles I was executed in front of the banqueting hall at Whitehall Palace, London on January 30, 1649. When the executioner held up Charles’ severed head to the crowd, he did not say the traditional “behold the head of a traitor.” Immediately following the execution the crowd rushed the scaffold to get relics.

After the Restoration, where the monarchy was re-established in 1660, Charles was declared a martyr and saint by the Church of England in 1662. He would be the last person canonized by the English church. Those who signed the death warrant of Charles I, and there were 31 of the 59 living at the time, regretted their signatures: six of the commissioners were tried and hanged. Oliver Cromwell, the “Lord Protector” of England who died in 1658, was disinterred and hanged anyway, with his body made to face in the direction of Whitehall Palace.

A devotional cult was established in Charles’ name and he is considered an Anglican martyr, especially by Anglo Catholics. It is said that if Charles had been willing to abandon the church and give up the episcopacy he might have saved his throne and his life. Charles would not give to either demand, and as Gladstone said, “it was for the Church that Charles shed his blood on the scaffold.

Charles was removed as a saint from the calendar in 1859 but his feast day continues to be observed in the Church of England. The Society of King Charles the Martyr continues devotional activities in his memory, which can be found here.

Charles is commemorated in churches across England and his last word of “REMEMBER” can be found on statues. A hymn written to St. Charles contains this verse:

“For England’s Church, for England’s realm (Once thine in earthly sway), Lest storms our Ark should overwhelm, Saint Charles of England pray!”