In Parts I, II and III we discussed the events and issues leading up to the passage of the Act of Supremacy, which caused the English church to break ties with the Pope and Roman Catholic Church. In this post, we’ll discuss what happened afterward during the rest of Henry’s reign.

The Act of Supremacy was passed in 1534, separating the English church from Rome and placing the monarch as the head of the church. Opposition to the Act was punishable by death, as witnessed by the executions of Sir (now Saint) Thomas More. More, who became Lord Chancellor after Cardinal Wolsey’s fall from grace, and (also a saint)

Bishop John Fisher, a leading opponent of the breach with Rome refused to swear allegiance to Henry VIII as the head of the English Church. Fisher was executed in June of 1535 and More was executed in July of 1535, declaring on the scaffold that he died “the king’s good servant but God’s first.”

In January 1535 Thomas Cromwell, Henry’s Chancellor, became Vice-Regent in Spiritual Affairs, which allowed him to continue working on reforming the church of England. In 1536 the Dissolution of the Monastaries began. Lands were seized and sold to the nobility, who, its was reasoned, would be reluctant to support a return to Roman Catholicism if it involved giving up their land.

The dissolution did not go unnoticed among the locals, however, and in the north of England there was an uprising known as the Pilgrmage of Grace. This was a quite bloody uprising and is worthy of a post in an of itself, as is the Dissolution of the Monastaries.

So what happened theologically? In 1536 Parliament passed the Ten Articles which was a compromise, of sorts, between Catholics and the reformers. The sole sacraments were Baptism, the Eucharist or Holy Communion, and Penance. Purgatory became a non-essential doctrine. The prayers for the dead and calendar of the saints was continued, although some saints were left off the calendar.

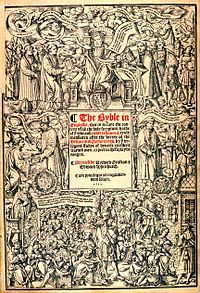

Most important during this time period was the requirement that a Bible in English was required to be kept in all churches. The “Great Bible” was a modification of the English

Bible by Miles Coverdale. This was replaced by the King James Bible in 1611, however the Coverdale Psalter can still be found in the 1928 Book of Common Prayer.

After the Ten Articles Cromwell continued to enforce reforming principles in England including destroying statues, images, and even the shrine of St. Thomas Becket in Canterbury.

All of this did not escape Henry VIII’s attention. Remember Henry was a contended Catholic and the direction of the English church troubled him. This was not lost on Cromwell’s opponents, of which there were many. Henry was also not very happy with Cromwell’s role in his arranged marriage to Annie of Cleves, whom he did not like.

Finally in 1539 the reforms were reversed with the passage of the Six Articles. Transubstantiation in the Eucharist, or the Catholic doctrine that Jesus is actually physically present in the consecrated bread and wine was upheld, the laity were not to be given wine at communion, clerical celibacy was enforced, monastic vows were to be honored, and confession was retained.

Cromwell fell from favor with Henry and was executed in 1539. There was no new Vice-Regent for Spiritual Affairs. Other events such as war with Scotland and France stalled any reform efforts.

Henry VIII died in January, 1547. At the time of his death, very little had actually changed. Mass was still said in Latin, communion was in one kind (bread), clerical celibacy was requirement and the traditional Catholic understanding of the seven sacraments was upheld. What had changed, though, was quite important. A lay person was the head of the Church. The clergy was subject to the laws of Parliament and Parliament had legislated religious doctrine.

It would take a new King, the “boy King” Edward VI, with a Regency Council of nobility who were sympathetic to the ideas of the Reformation, for the English Reformation to proceed further. With Cromwell gone, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer would step forward to lead the next stage of the Reformation, and that will be explored in Part V.